More pesticides, more genetic engineering: How we are overcoming hunger.

Around 1800, almost everyone was still living just above the subsistence level. When I say everyone, I mean everywhere: in Africa and South America, in China and India, in North America and yes: in Western Europe - even in Switzerland, which was already considered comparatively "rich" at the time. Most people had lived from agriculture for a good 10,000 years, they worked as farmers and therefore depended on their seeds, the land and the weather. One bad summer, one bad harvest, one war was enough to cause hundreds of thousands to die. They starved, they died like flies.

Tuesday, November 14, 2023

The facts: Fewer and fewer people are poor, fewer and fewer die of hunger.

There are three reasons why this is important. 1. innovation. 2. innovation. 3. innovation.

Many Swiss people probably don't realise how poor we all used to be:

- Back in 1800, almost everyone - I emphasise: everyone - lived just above the subsistence level. When I say everyone, I mean everywhere: in Africa and South America, in China and India, in North America and yes: in Western Europe - even in Switzerland, which was already considered comparatively "rich" at the time

- Most people had lived from agriculture for a good 10,000 years, they worked as farmers and therefore depended on their seeds, the land and the weather

- One bad summer, one bad harvest, one war was enough to cause hundreds of thousands to die. They starved, they died like flies

This has changed dramatically over the past two hundred years

First in the West - i.e. Western Europe and North America, then in Japan, Korea and the whole of Asia, and finally all over the world, prosperity increased almost year on year. Not even the two world wars, the most devastating wars ever, or the economically pointless arms race during the Cold War could change this.

If millions were still dying of hunger in China in the 1950s (and because of the communists, who were responsible for this wrong agricultural policy); if poverty still seemed so persistent in India in 1970 that serious Western scientists thought it was solely due to "exaggerated" population growth there, which gave rise to dark fantasies, then we are in a completely different place today:

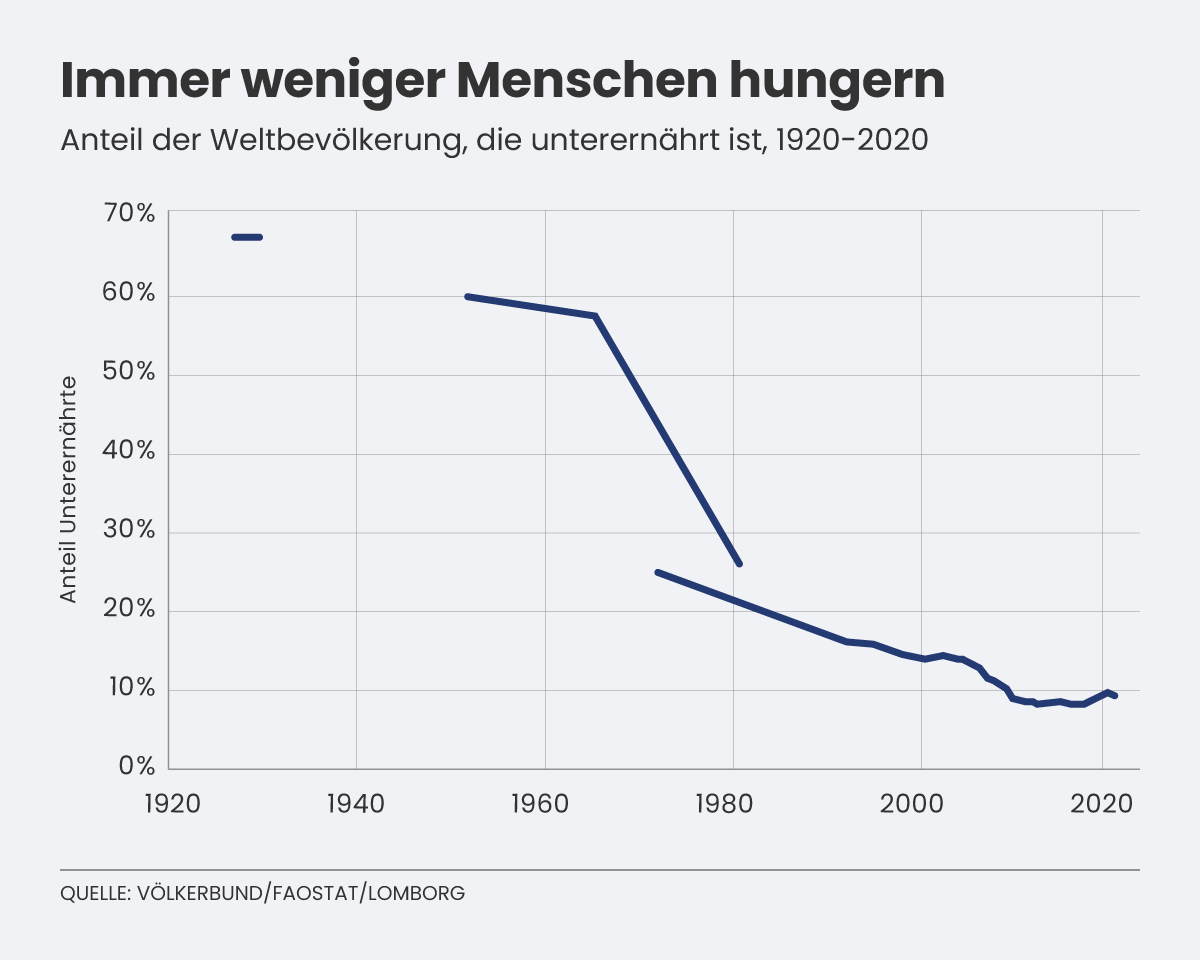

- In 1928, the League of Nations (the predecessor of the UN) estimated at the time that more than two thirds of humanity suffered from malnutrition: they were constantly starving. Two thirds!

- Since then, this death rate has fallen spectacularly: in1970, according to the FAO, the UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation, "only" a quarter were starving

- In 2017, 8.2 per cent of humanity was still affected by malnutrition. However, this figure has since risen again due to the pandemic and the war in Ukraine: in 2022, it stood at 9.3 per cent

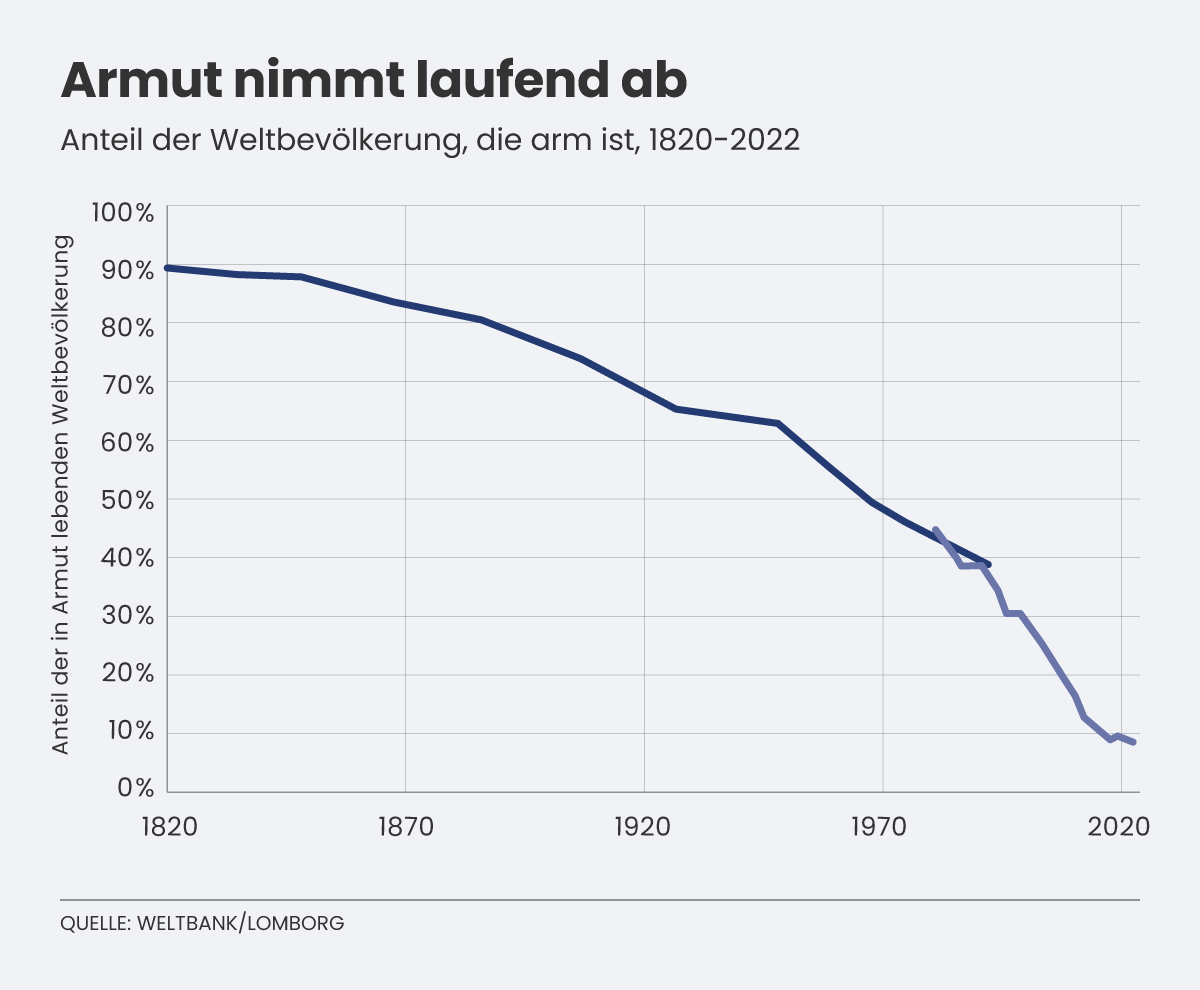

Even if we look at the global development of poverty, which is of course closely linked to nutrition, the same picture emerges:

- In 1820, around 90 per cent of humanity was considered poor

- Today, according to the World Bank, this proportion is less than 10 per cent

And even that doesn't have to be the case, as Björn Lomborg explains in his latest book: Best Things First. It was published a few weeks ago. (See the three-part article by Alex Reichmuth, here, here and here).

Lomborg, a Danish political scientist and statistician, can perhaps be described as one of the most creative thinkers of our time. On the assumption that we are setting the wrong priorities worldwide when it comes to the challenges facing humanity, he and a think tank associated with him (Copenhagen Consensus Centre) are trying to calculate in francs and centimes which measures will do the most good.

To this end, he has called on renowned scientists from all over the world to analyse this question in scientific papers: What is the best thing to do first?

As far as the plague of hunger is concerned, he and the experts are convinced that an investment of $74 billion - spread over the next 35 years - would be enough to largely eradicate hunger. How?

- The money would have to flow mainly into research and development, in short: into innovation

- Everything should be done to ensure that the best genetic engineers, chemists, molecular biologists and agricultural engineers search for new technologies for agriculture in order to increase yields per hectare

- Specifically: even higher-yielding seeds, smarter farming methods, more effective irrigation systems, more efficient pesticides, etc.

This may sound like a no-brainer, but it is not, especially as technological progress in agriculture and nutrition is often hindered for political reasons - opposition to genetic engineering is just one of the grotesque, esoteric examples (there is no scientific evidence that genetically modified plants are harmful to us).

If we look at the past - and in particular the success story since 1800 - there is no getting round it:

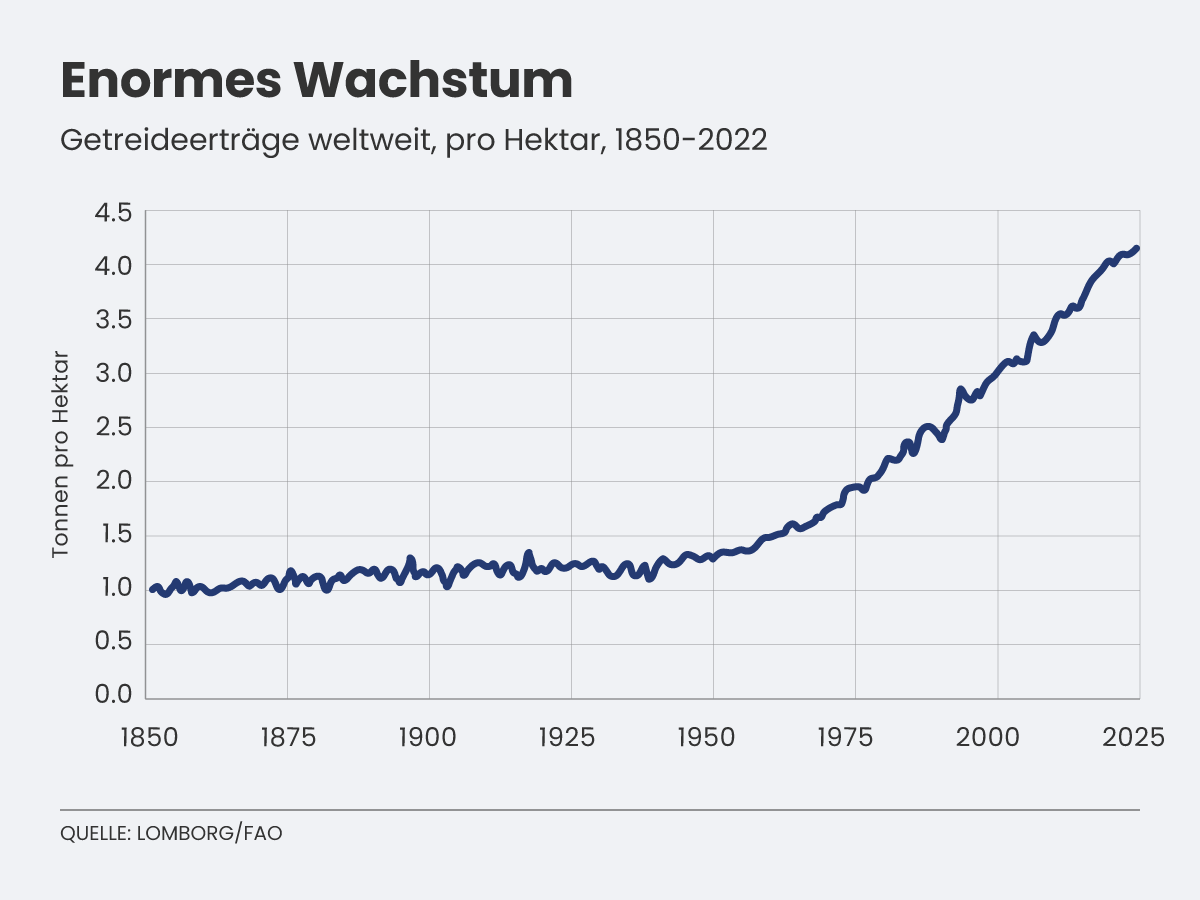

- It was primarily innovations in agriculture that pushed back hunger

- By farmers (especially in the West) getting more and more out of every hectare of land, so that more and more people can be fed

- Without using much more land: global grain production has increased by 249% since 1961, while the area under cultivation has only increased by 12% at the same time

This was the "Green Revolution", as it was soon called, when better fertilisers, new pesticides and more productive seeds performed a miracle the like of which had probably not been seen since the legendary multiplication of bread on the Sea of Galilee.

Back then, a certain Jesus Christ was responsible for this. Today, we have it in our hands to trigger a second Green Revolution. At a cost of $74 billion.

Or to paraphrase an old German proverb:

"If you have no bread, you'll probably make do with a pasty."

Kindly note:

We, a non-native editorial team value clear and faultless communication. At times we have to prioritize speed over perfection, utilizing tools, that are still learning.

We are deepL sorry for any observed stylistic or spelling errors.

Related articles

ARTE documentary: Genetic engineering in organic farming?

The ARTE documentary “Genetic engineering in organic farming?” examines key controversial questions of modern agriculture: Is the general exclusion of new breeding technologies still up to date? Can the resistance of organic farming be justified scientifically?

Why consumers accept gene-edited foods on their plates

Acceptance of gene-edited foods increases when their tangible benefits are clear to consumers. Studies show that visible advantages for health, the environment or food security are key to public support.

Genetic Engineering in Everyday Swiss Life – “There’s a Gene in Everything!”

The genetic engineering moratorium in place since 2005 gives the impression that Switzerland is largely free of genetic engineering. However, a closer look shows that genetic engineering has long since become part of our everyday lives – we just usually don’t notice it.

The Great Suffering of Farmers

Fire blight, Japanese beetles, or grapevine yellows – farmers in Valais, too, are increasingly feeling helpless in the face of the threats posed by nature. More and more often, they lack the means to effectively protect their crops. This makes it all the more important for the Federal Council to place a pragmatic balancing of interests at the forefront when setting threshold values.