Reason Over Ideology: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Rejects a Blanket Ban on Genetically Modified Organisms – A Victory for Science

Stephanie Lahrtz is a science editor at the NZZ and writes about scientific topics such as modern biology, ecology, and medicine. She welcomes the fact that the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is opposing a general ban on the release of genetically modified organisms.

Monday, October 20, 2025

As the world’s largest conservation organization, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has positioned itself against a general ban on the release of genetically modified organisms. This decision, adopted on Wednesday at the annual assembly in Abu Dhabi by member representatives from ministries and non-governmental organizations, is good news: sound scientific arguments have prevailed over anti-GMO ideology.

Consequences of a Ban

A call for a ban by the IUCN would not have had any immediate legal effect on research or release experiments around the world, since the organization does not legislate. Yet, the IUCN is highly influential.

Many of its recommendations and resolutions are incorporated into national legislation or shape the strategies of conservation projects. Expert groups of the IUCN, for example, compile the Red Lists of threatened animal and plant species, which guide governments when designating nature reserves or enacting protective measures.

A general call to prohibit the release of genetically modified organisms would therefore have had powerful symbolic significance. It would have armed certain environmental groups — long opposed to GMO animals and plants — with fresh ammunition. And it is likely that many countries would have invoked such an IUCN position when evaluating local release projects.

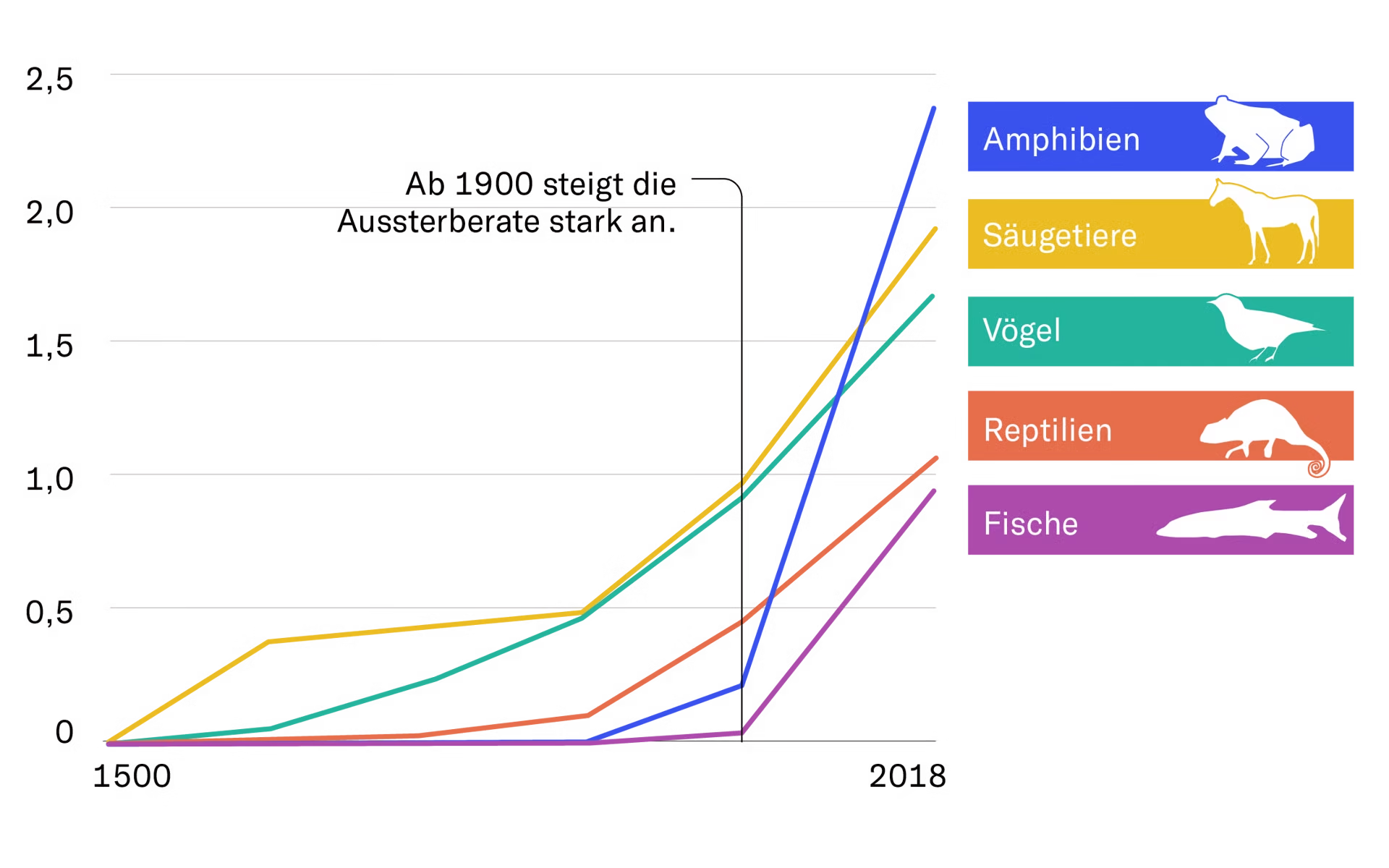

If nations were to impose total bans on the release of genetically modified organisms, it would block important conservation innovations. Researchers are, for example, working on genetically modified frogs resistant to a deadly fungus that has already wiped out millions of amphibians worldwide. Others are developing sterile rats; on many islands, invasive rats introduced by humans have devastated local bird populations, pushing endemic species to the edge of extinction. The list of such projects could go on

Of course, it remains uncertain whether these genetic approaches will ultimately succeed. But researchers must be allowed to test them under strict safety protocols — particularly when no viable alternatives exist or previous methods have failed.

IUCN Chooses Science Over GMO Fear

The ban had been demanded by numerous environmental organizations as well as representatives of Indigenous communities. They share a long-standing fear that the release of genetically modified organisms could have unforeseeable consequences. They argue that GMOs are insufficiently tested.

It seems, however, that some GMO opponents do not want research or testing to occur at all. Perhaps they fear losing their image — and their donation revenue — should trials demonstrate that some GMOs are both useful and harmless, and that this much-maligned technology is not nearly as dangerous as often claimed. Indigenous groups, for their part, worry that they could lose control over their environment to large corporations or foreign research institutions.

Many of these concerns are legitimate. Yet those who advocate field experiments with genetically modified organisms are not seeking a free pass. No one wishes to see unregulated releases of lab-engineered rats onto islands at random. In many countries, extensive pre-screening and approval procedures for GMO releases are already enshrined in law.

These rules effectively prevent reckless and meaningless releases. The IUCN General Assembly has therefore rightly opted for a balanced strategy — one that trusts in scientific evidence rather than fear-based ideology.

Stephanie Lahrtz is a science editor at the NZZ and writes about topics in modern biology, ecology, and medicine.

This article first appeared in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung on October 18, 2025.

Kindly note:

We, a non-native editorial team value clear and faultless communication. At times we have to prioritize speed over perfection, utilizing tools, that are still learning.

We are deepL sorry for any observed stylistic or spelling errors.

Related articles

Pesticides in Green Smoothies

After countless recipes for Christmas cookies, festive roasts and cocktails, the advice on losing weight, detoxing and beautifying oneself now takes centre stage. Most of it is sheer nonsense.

Natural Toxins: An Underestimated Risk in Our Food

Safe food cannot be taken for granted. While chemical substances are often the focus of public criticism, reality shows that the greatest risks to food safety are of natural origin. Recent recalls of infant food products illustrate how insidious bacterial toxins or moulds can be.

Herbal Teas: Making You Sick Instead of Slim

Plant protection products are frequently the focus of public criticism. Far less attention is paid to the fact that natural ingredients in teas and dietary supplements are also biologically active and can pose health risks.

Why Strict GMO Regulation Stifles Innovation

New breeding techniques such as CRISPR-Cas are considered key to developing resilient crops, stable yields and reducing the need for plant protection products. ETH professor Bruno Studer warns that overregulating these technologies strengthens precisely those large agricultural corporations that critics seek to curb, while excluding smaller breeders and start-ups from the market.